![]()

160 participants gathered at the Danish Parliament in Copenhagen to identify a path for mobilizing resources for the world’s least developed countries. The conference was sponsored by the Human Act Foundation, co-founded by Djaffar Shalchi and Ané Maro, who also lead the Move Humanity Initiative to mobilize a 1 percent tax on the world’s billionaires to finance the SDGs. The conference was co-organized by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and ActionAid Denmark, and graciously hosted by MP Peter Hummelgaard and the multi-party 2030-Network of 65 Danish Parliamentarians.

Overview

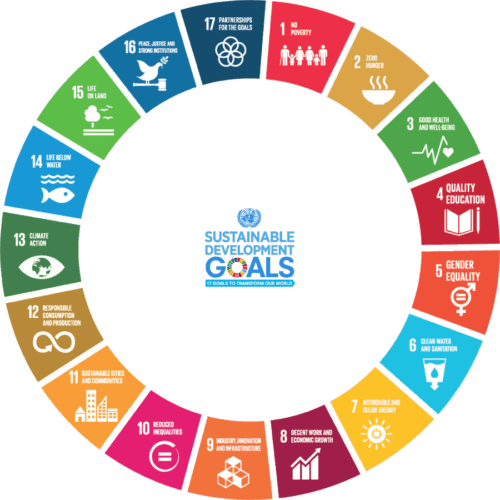

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a guiding roadmap for people, planet and prosperity. They provide countries with a broad set of targets and indicators for how to measure progress towards a sustainable and equitable future. In 2015, when the SDGs were adopted by 193 countries, the world agreed to leave no one behind.

The Move Humanity Conference was convened as an acknowledgement that a critical lack of funding, however, meant that many groups including women, minorities, indigenous populations and persons with disabilities, are being left behind, placing the world at risk of failing to meet the Goals by 2030. Participants acknowledged that progress towards the SDGs has been largely uneven between and within countries. This trend has driven and been exacerbated by rising income inequality in half of the world’s countries, undermining SDG achievement everywhere.

Participants discussed how income inequality goes hand-in-hand with other disparities, such as access to quality healthcare, access to education, political power and environmental justice. These disparities exact disproportionate impacts on vulnerable populations which threatens sustainable development, peace and security, and the undermines the work and mandates of the conference’s participating civil society organizations.

Conference participants agreed that achieving the SDGs will require governments, the private sector, and civil society to tackle inequality as a central barrier to sustainable development. This challenge speakers argued could be met with more extensive efforts to mobilize finance at both the international and domestic levels, acknowledging that this mobilization must first include a careful analysis of the many ways in which wealth accumulates globally and directly tackling those inequitable structures.

With Gross World Product standing at US $88 trillion, the world can finance the SDG’s. The resources are readily available yet unequally distributed. Over the course of the conference, participants identified principles and policies for mobilizing and equitably distributing development financing through aid, investment and taxation.

The SDG Budget Gap

In 2018 SDSN and Move Humanity prepared the report Closing the SDG Budget Gap which informed conference discussions and built on research published by the IMF in a 2019 Staff Report. Both reports find that the world’s 59 low-income developing countries (LIDCs) need less than 500 billion dollars to meet their core SDG financing needs, an average of an additional 15 to 19% of GDP. Even with increased tax revenues and spending efficiencies (which can cover approximately 5% of this gap), domestic resources will be insufficient to fill this financing gap.

The need fir external financing in low-income developing countries

Even with sustained growth over the next 11 years, increased domestic resource mobilization (DRM) and spending efficiencies, the achievement of the 2030 Agenda in LIDCs will still be dependent on external resources to augment domestic ones, such as contributions from Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Private Development Assistance (PDA).

It has now been 50 years since the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donor countries established the target that 0.7% of their GNI should be contributed to ODA. Still today the DAC countries contribute only 0.31% of their GNI on average. For the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors as a whole, a rise to 0.7% of GNI would raise an additional US $175 billion per year, most of which could be directed towards the SDG financing gap. It was largely agreed at the conference that the failure to meet commitments by a majority of donor countries calls into question their sincerity of achieving the SDGs for the world.

Increasing ODA flows is a significant opportunity to close the SDG financing gap and the need for additional ODA was identified as crucial to reduce the inequality between countries and meet the SDGs in the LIDCs. ODA must be better targeted to the least developed countries. In 2017, of the total US $146.6 billion in ODA flows, only US $26 billion went to least developed countries.

ODA must also be better targeted towards the social sectors where the private sector can and will not invest.

It was also emphasized that continued assistance should prioritize institutional capacity building and support for progressive tax reforms in order to promote financial sustainability in the long-term and to overcome the inequality crisis.

Public investment for public goods and the limitations of private finance

Panelists recognized that the SDG financing gap largely affects the under-production of government-provided public goods and services such as education, healthcare, social protections, and core infrastructure. In the absence of sufficient public revenue, many governments are turning to private finance to meet their budget needs. However, the absence of profits in many public sectors as a motivator to attract private finance, and, when it is available, the frequent lack of private finance’s coordination with national development plans means that services for low-income, vulnerable populations too often go unfunded.

According to the OECD, from 2012-2015 official development finance unlocked $81 billion in private finance for development globally, yet less than 7% of the total went to least-developed countries, and only a very limited portion of these funds targeted the social sectors.The private sector can certainly play a crucial role in meeting the SDGs, particularly in areas such an industry innovation, responsible consumption and production, gender equality, decent work, economic growth and others. However the international community should be cautious in overprivatizing development.

Private financing addresses the needs of those with some ability to pay for goods and services, generally those at the higher ends of the income and wealth distribution, but ignores those at the low end of the distribution. Privatization as the “solution” would be tantamount to leaving hundreds of millions of people behind.

Progressive tax reforms

Progressive tax schemes implement a higher tax on capital income rather than labour income. However, since the 80’s the world has witnessed a steady downward trend of lowering taxes on capital income, resulting in exponential increases in private and personal wealth.

The distributional impacts of various tax reforms are crucial in order to ensure that the tax burden is primarily carried by the wealthier segments of the society. Participants saw interesting plans for this in Denmark and other developed countries as well as proposals for how to implement progressive tax reforms in developing countries. On many occasions references were made to the Danish and Scandinavian experiences of creating a welfare state based on relatively high and progressive taxes, public financing of education, health and core infrastructure and a strong social safety net.

The increased taxation of wealth would produce substantial revenues for the SDGs and can be more strategically used a public finance tool. The Move Humanity report identified that the roughly 2,200 dollar billionaires of the world have a combined wealth of approximately US $10 trillion. This number simultaneously illustrates extreme global inequality as well as the availability of resources for meeting the SDGs. A global tax on 1% of billionaire wealth per annum would yield around US $100 billion. This would cover a significant portion of the SDG financing gap of the 59 LIDCs.

If the hypothetical tax base were to be broadened, even further progress could be made. There are an estimated 256,000 individuals worldwide that are worth between US $30 million up to US $1 billion. Their combined net worth is around $32 trillion. A 1% wealth tax on these ultra-high-net worth individuals would raise on the order of US $320 billion per year. This could nearly close the SDG financing gap of the 59 LIDCs.

Similarly, other progressive tax strategies can be considered to mobilize and redistribute resources such as a carbon tax, financial transaction tax, and offshore account tax. These new forms of taxation, if earmarked in part towards increased ODA for the SDGs, would improve global resource allocation, bolster economic fairness, and help to close the SDG financing gap for LIDCs. A specific outcome of the conference was the ambition to promote a UN resolution calling for such taxes to close the SDG financing gap and simultaneously reduce the inequalities in and between countries.

Ending tax havens and tax evasion

Wealth taxes and other progressive tax strategies cannot succeed unless the tax haven industry is tackled and financial transparency is mandated. Illicit financial outflows are currently taking place in an international system that facilitates these activities by design. The OECD estimates that tax havens are home to US $20 trillion or more in offshore deposits.

It is estimated that the global loss to governments from profit-shifting by multinational companies is upwards of US $500 billion per year. As a percentage of their gross domestic product, developing countries are hit hardest.

The world needs decisive, corrective action on this front. The long-term goal must be to push for closing tax havens and ending loopholes in the global corporate tax system.

The developing country context

Taxed citizens in developing countries want to start benefiting from returns on their taxes that are roughly commensurate with their contributions in order to perpetuate a willingness to pay. However, it is often the case tax revenue-reliant social services and strong and reliable infrastructure that could be funded through taxes are nowhere to be seen or extremely limited. Underpinning this issue is poor governance, corruption and misdirected use of revenues. There will be a continued effort in developing countries to ensure governments deliver for their citizens in ways that validate their taxation policies in order to build significantly greater trust in a social contract.

It was also a point of focus to be more persistent in addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). This refers to tax avoidance strategies that exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to artificially shift profits to low or no-tax locations. Representatives from the global south advocated for a global process to capture wealth and stop the aggressive behavior of companies taking advantage of creating economic activity in their countries without physical presence.

Participants advocated that the increase of development assistance in developing countries must also be paired with strengthened governance, sustained equitable growth and proactive budget allocation of resources to key SDG sectors.

Philanthropy is an important and growing, yet insufficient, source of development finance

Based on available data from 143 foundations, an OECD survey found that private foundations provided US $23.9 billion for development from 2013 to 2015, averaging US $7.96 billion per year. This amount will likely continue to increase as a global average.

As wealth continues to accumulate, philanthropy was discussed as an important contribution to financing the SDGs. Some ultra-high net worth individuals contribute significantly to financing core SDGs, their study and their advancement. However, the goodwill of wealthy individuals and/or private companies alone is an unreliable and insufficient source of resources for filling the SDG financing gap. One major critique of philanthropy is that it does not challenge the power structures of the wealthy and perpetuates top-down models of elite influence. Philanthropy allows for donors to contribute to areas and sectors they are most interested in, which may not always be the areas most in need. Philanthropy as a tool for advancing the SDGs is most effective when aligned with national development plans and SDG needs assessments. To optimize for the impact of high net-worth individuals’ contributions to SDG advancement, discussants raised the prospect of implementing a tax on wealth, the allocations of which would be allocated for accountable and development-related spending.